What Happens When 1,000 Strangers Talk Race In L.A.

LAURA BLISS |

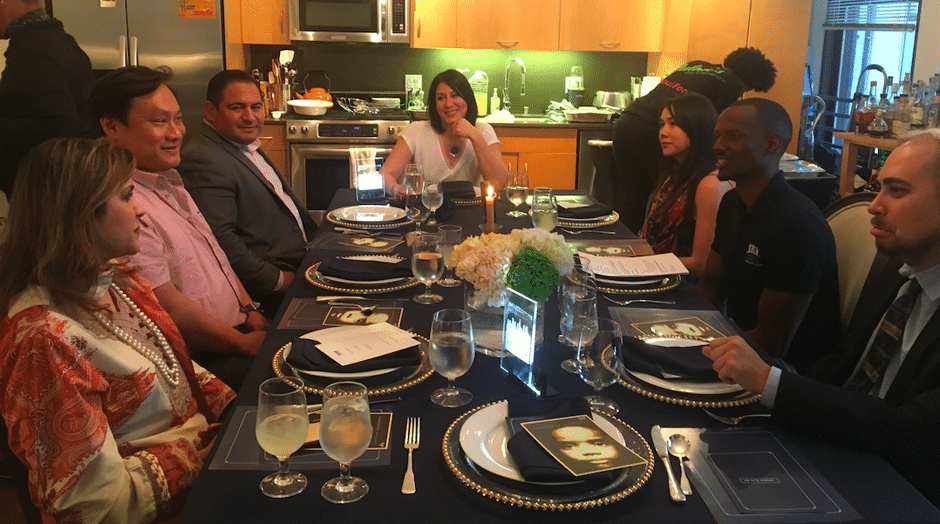

Angelenos gathered at 100 dinners this week through a city-backed initiative to spark civic and civil dialogue.

“We’re not all having dinners together.”

But with a fraying social safety net, affordability doesn’t equal stability, said Emily Coldiron, a program manager at a nonprofit that works with children. Coldiron, who’s multiracial, drew on her experience being raised in Wichita, Kansas, by a single mother who faced multiple evictions. “I think the U.S. as a whole has this approach of, ‘Oh, you’re having a problem, this is your fault, you need to deal with this on your own,’” she said. “There’s just not a lot of support. We’re not all having dinners together.”

Coldiron’s point seemed to hit on a possible limitation of these dinners: At least for now, they’re self-selecting. A number of participants at Tuesday’s meal remarked on this, acknowledging that everyone at the table came with a range of generally progressive political views. Each participant also happened to identify as a person of color. That wasn’t on purpose, Rodriguez said, but “merely reflected L.A.’s diversity.” Most had professional backgrounds in nonprofits, mental health, medicine, and law.

In some ways, hosting a table of politically like-minded individuals was productive, Foster said when asked after the dinner ended. People tend to be open up more when they know they won’t be attacked or critiqued. On the other hand, he noted, there may have also been a benefit to having more conservative attendees, people who are less educated on racial issues, or indeed, more white people, at the table. “It would have been interesting to work through these issues with folks who aren’t already aligned with what we’re trying to do,” Foster said.

In the future, he thought that city council could do targeted outreach to bring even more diverse voices to break bread. Rodriguez said that this is a possibility for future series—and that this was just one of 100 dinners.

Still, a number of Tuesday night’s diners said afterward that they felt more empowered to talk about race with other people in their lives. Hom said that he had come to the dinner expecting to find more divisions than shared experiences. But he left feeling like he had more in common with his fellow Angelenos than not. With that knowledge, “tomorrow, I feel like I can start working on making things better,” he said. Participants had come up with many strategies for building a more cohesive, compassionate L.A.: visiting unfamiliar neighborhoods, voting in diverse political representation, speaking up when a fellow human is being harassed, volunteering for social causes, and even watching TV shows that subtly bridge social divides, like “Queer Eye.” (“That show is kind of mind-blowing,” said Tom Chang, a former mental health professional whose family immigrated to the U.S. from Taiwan.)

As the night came to a close, caterers washed dishes as Perez packed up leftover cheese and crackers to send home with willing takers, and a few diners lingered to keep chewing over dangling threads of the conversation. No, the dinner did not produce radical solutions to move more people off the streets—nothing akin to Mayor Eric Garcetti’s declaration of a “shelter crisis” the same day. But Foster felt that the conversation might have nudged some hearts and minds by talking about the how people find themselves living in homelessness, and how structural racism may play a role. He expressed hope that these participants will now feel more empowered to spark their own conversations with other people in their lives.

The next night, Foster would guide a conversation among a much larger—and whiter—group near Malibu. But no matter the racial makeup of the participants, he said, “with issues that are so huge and institutionalized, people are going to shift their views on a one-by-one basis,” he said.

The key was to keep faith in dialogue. “Whether they’re like-minded or not,” he said, “just having a conversation begins many more like it.”